- Posted on

⚠️ Please read with care: This blog shares personal, sometimes painful experiences. My intention is to support and speak honestly not to harm. I’m not a professional, just someone who understands how hard it can get. If you're struggling, you're not alone please reach out for professional help.

So, my father’s funeral was last week. Cue the violins. Strange thing, really I only met him in 2000, yet somehow, in those short years, he managed to make more of a mark than most of the so-called “family” I was genetically blessed with. At the service, people spoke about his achievements with such pride that I wasn’t sure if I was supposed to cry or applaud. In true British fashion, I did neither and quietly pretended my sunglasses weren’t hiding the chaos underneath.

Our relationship didn’t exactly come with a neat bow. Coincidences dragged us together, the sort of cosmic joke I’ve been the punchline to since childhood. I can’t shake the feeling that I’m being nudged along by some unseen force God? Fate? Or just some drunk bastard with a clipboard? Either way, the path has been there, whether I like it or not.

And then there’s the juicy bit. I learned that my father didn’t want me and my sister adopted, that he wanted to marry my mother. Sweet, right? Except my mother turned out to be a block of ice wearing a dress. When I was at my weakest my multiple sclerosis ripping chunks out of me I sent her emails, desperate for a scrap of warmth. Her replies? none to busy. Apparently, my pain was an inconvenience to her daily routine of… what, exactly? Cold tea and colder emotions.

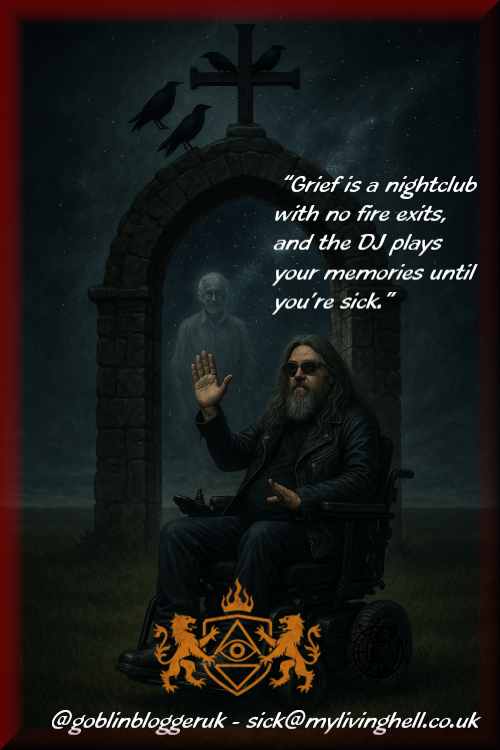

Family gatherings? Imagine being the cuckoo in the nest except all the other chicks had already decided I was the intruder. That’s been my life. When my mother died, nobody thought to tell me anything beyond the bare minimum. No funeral details, no warmth, no seat at the table. Just silence. I didn’t go, not because I didn’t care, but because by then I was already the ghost in their machine.

Now here I am. Technically one of eight, yet alone in a crowd. My father who I only recently discovered was a biker rides on in memory, while my mother remains a cold shadow I choose not to revisit.

The truth is this: family is overrated. Blood ties are just plumbing. What matters is the path you carve when no one’s got your back. Mine is messy, full of MS battles, funerals I don’t attend, and ghosts that don’t answer emails. But it’s mine, and I’ll keep walking or rolling down it.

So, here’s to the outsiders, the cuckoos, the ones who got left behind and kept going anyway. If that’s you, pour a stiff drink and join me in this dark little corner of honesty. Misery loves company, but at least we can laugh at the absurdity of it all.

I write in ink and fury, in breath and broken bone.

Through storm and silence, I survive. That is the crime and the miracle.